Winter Resident Orcas

The winter has a hard, cold grip on the north coast of BC these days. A strong arctic front is hampering our research area for more than a week now. Strong northeasterly outflow winds are being funnelled through Douglas Channel and Whale Channel. Temperatures are well below freezing which makes it difficult to keep warm. So to hear resident Orcas on our hydrophone in Whale Channel a few days ago, was a welcome surprise and filled our hearts with excitement. A4s and A5s were audible and though they started out faint, their calls became louder fairly quickly. It turned out that the whales were on their way south and it did not take long before they were in sight. It did not matter how cold it was, I had to go out in the boat to see who was there. I caught up to the whales as they were travelling by the seaweed camp of the Gitga’at in Casanave Pass. They were spread out and travelling fairly quickly. As soon as they entered the open water of Campania Sound they started to forage and were spread out in an even greater area. Needless to say that there was no way for me to try to get ID pictures of every whale present. Instead I decided to just idle along and watch the whales from a distance. All over sudden I heard two blows right behind the boat. A juvenile and calf had come over to the boat and decided to check me and Neekas out. It was one of those encounters that I will never forget in my life. Those two curious young whales stayed with me for 20 minutes as we travelled at about 2-3 knots. They would dive under the boat, turn upside down then surface right next to the boat, so close that the mist of their blows would cover my face. I could see their whole bodies below the clear water surface. So unbelievably beautiful. Neekas was busy running back and forth to catch a glimpse of the whales, she really enjoys the company of Orca as well. It was only after the two curious whales left that I noticed how cold it actually was. I was now in the middle of Campania Sound in an open boat and had to go back home facing the cold arctic winds. It took me a long 30 minutes to get back home and I was frozen to the bone but the encounter was well worth it and after reviewing the pictures I was able to find out that the matrilines present were:

A24s, A43s, A51s and A35 plus Springer. There might have been even more.

Meet Caamano Sound

Recently, a private members bill from NDP MP Nathan Cullen was voted on in the House of Commons. The Bill was seeking a Ban on Oil Tanker traffic along the North Coast of BC. The vote was in favour of the Ban with all opposition parties voting for the Bill. However, our Conservative Government voted against the tanker ban and because the vote is non-binding it will be hard to pass the bill through the legislature. But the vote did show that a majority of our politicians are supportive of the Tanker Ban, which is extremely good news.

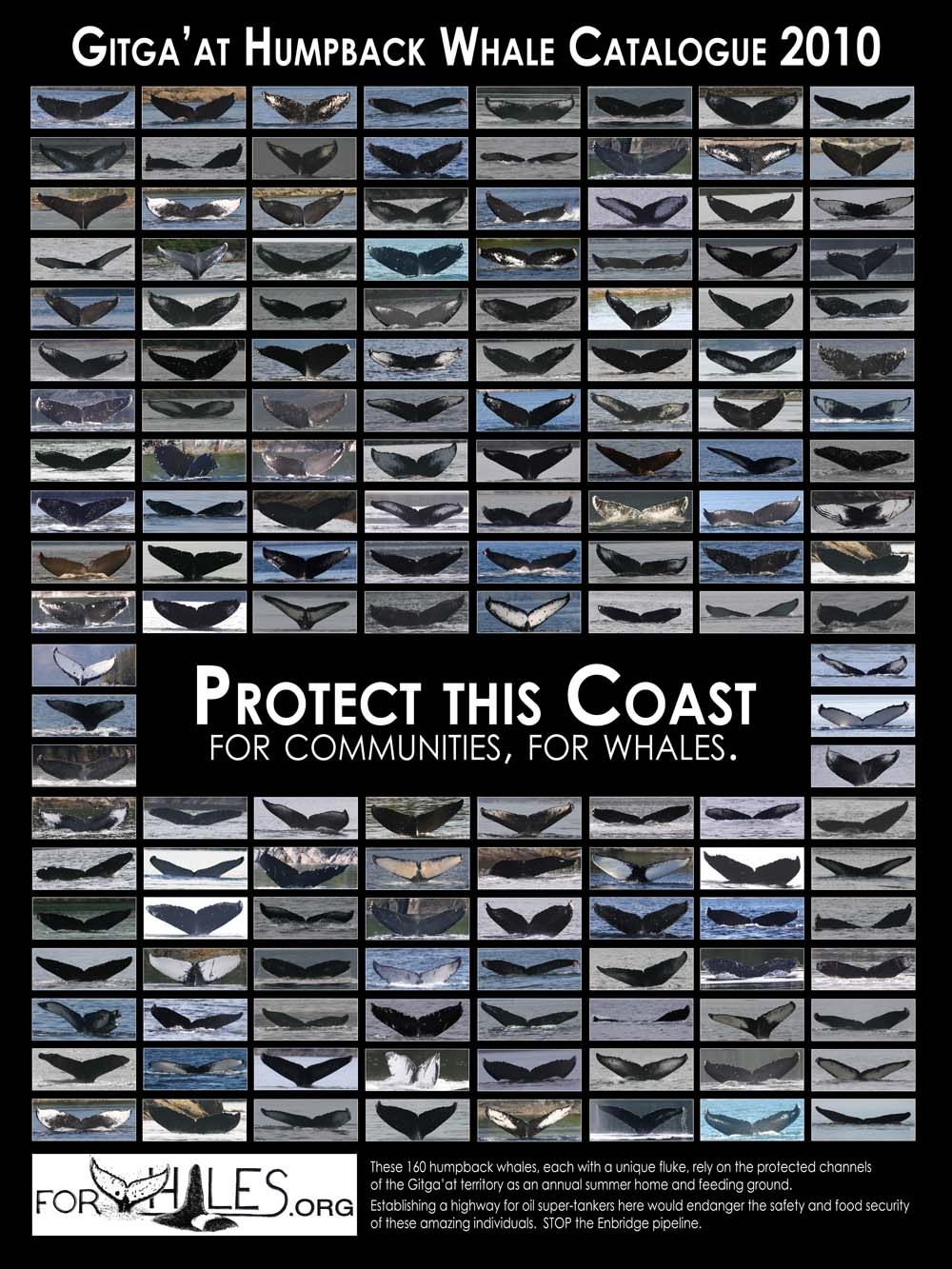

Please read this poster, created by our friend and co-researcher James Pilkington. This poster displays the beauty of Caamano Sound and describes very well what would be at stake should Oil Tanker Traffic be allowed to destroy the waters of this pristine area.

Let’s keep the North Coast of BC Alive and Safe for all Marine Life!

Humpback Whale Catalogue 2010

Take a look at our Humpback Whale Catalougue from 2010. We are just getting ready to publish our 2011 Catalogue and can expect to add at least 20 new resident humpback whales to the list!!

An Acoustic Masterpiece

It began at 6am, a few faint calls on the hydrophone station right in front of the lab. They were humpback social calls and quite faint. We started the recording; I put on the head set so I could hear them more clearly. With our mixer we are able to position different stations to be heard in different ears, so in this instance I was listening to the Whale Channel Station in my right ear, The Home Station was in the center, therefore I could hear whales in both ears, and Money Point Station, which is up north near Hartley Bay, was in my left ear. This is a great way to track if there are other whales present besides the one that may have first alerted us to the presence of a cetacean (note - cetacean is the Latin word for all dolphins, porpoises and of course whales). So while I am listening to this lone humpback somewhere in front of the lab, in complete darkness as the sun has not yet peaked over the mountains, and who would see it anyhow with all this rain, I heard another very familiar call – Orca!! They were resident calls of the A4 pod, and later we would realize the family of the A24s. So the first strokes of what would become an acoustic masterpiece were just beginning, and I had not even had my first sip of caffeine. I was also aware that I was shivering from the early morning dampness as there had not been time to start the fire. I let the recording run and quickly chopped some kindling; soon there was the sound of wood crackling and the first perk of a fresh pot of coffee. With my hands warming from holding this cup of java I listened as orca sang in the center with the odd social humpback call in my right ear. I am not sure if the humpback whale could hear the orca chatter, but soon the humpback went from a few social calls every couple of minutes into a glorious song for all the creatures of the marine world to listen to. This included the family of orcas, or so I assumed as they were suddenly very quiet. Were they also in awe of this acoustic wonder, curious as to which neighbour could make such cry’s, do they realize this is a humpback whale? We may never know, but this moment of silence from these resident orcas was short lived and soon they were back into chatter mode. I was not sure which station to keep in the center, how does one choose between a humpback or orca call? The whales made the decision easy as a 3rd group decided to become involved. Now alongside orca calls on the Whale Channel station there were more humpback calls, but not song, not social, but feeding calls and they were close. If this was not enough, between orca social calls, humpback song and feeding calls, in the distance there was a 4th humpback that also decided to go into song. I was writing so fast, trying to keep up with this acoustic masterpiece I almost forgot the one most important thing.....to listen.

How Fast Everything Can Change

How can everything change so fast? One minute a wall of rain so thick is falling from sky to a glorious moment of sunshine. It has been a week since we had even seen the sky, oh that forgotten blue truly is the most beautiful sight we have ever seen. Then, just like that, transient killer whale calls were heard over the hydrophone. They haunted us for hours, cry after cry, in Whale Channel. We had only our imagination to tell us what they could possibly be feeding on, the excitement was obvious. We searched from the lab to spot a blow, and were not disappointed. A few km to the south, outside the seaweed and halibut camp of Hartley Bay, we could see 2 blows. Unfortunately, we were not able to use our boat as it was high on the beach from the previous storm. Later today, at high tide, we still dare not go out on the water, as yet another storm was in the forecast. These blows were not the group of transients, but 2 humpback whales. They were be traveling towards the direction of the transient calls, and within 30 minutes out of our view to the north. It has been observed when transients make a kill, with humpbacks in the vicinity, often they will travel in closer to see what is happening. To date they have never interfered and appear to only be curious. There could be many reasons for this behaviour that we are completely unaware of. What we see as curiosity could in fact be a warning from the humpbacks towards transient killer whales to leave their kind alone. This is another mystery of many which makes our job of trying to interpret their behaviour all that more challenging and exciting.

Weathered

Seagulls fly, waves roll, one after the other, then crash as the moon pulls the ocean away from shore. This is the scene I am watching as light begins to fill the sky of early morning. It will be difficult to find whales today in this turbulent sea. The wind is still blowing at about 30 knots, the windows are shaking leaving me in doubt whether I should even be out here in the lab. I often wonder what whales think of such weather. Do they celebrate the opportunity to play in this aquatic chaos or are they so intent on finding food they travel further inland, to calmer waters to forage. Since these storms have arrived, one after the other, we have not heard a peep over the hydrophone stations. What we are listening to instead is an imitation of white noise from the constant movement of water. Perhaps this underwater mayhem of sound, vibrating off the rocky shoreline, is a deterrent when trying to locate food or to sing as humpbacks generally do this at this time of the year. As the days become shorter and humpback whales have gorged themselves on fish since spring, the singing begins. Only the males will sing and even to this day the reason why is still not clear. While you listen, the reason becomes irrelevant as each call resonates through a sacred place that is within us all. Last year at this time we had already recorded 100 hours of humpback whales singing. But last year was very different than this one. For one thing the weather, until the end of October we had sunshine and calm waters almost every day. Posturing groups were forming right here in Taylor Bight, groups of 3 to 5 males showing their true might. We were no longer witnessing cooperative bubble net feeding, as we were here just one week ago. Yes, nature has its own beat, to predict one year from the last would be mistake indeed. All one can really do on days like this is to sit back and enjoy the storm.

Solitude with Whales

All the tents are gone, KPL has towed out for the season, the radio chatter has almost disappeared and Hermann and Neekas have gone to town for a few days. I had thought I would have welcomed the silence. Instead, I felt challenged to be left with only my thoughts, my voice, the only human standing here on this entire island. I walked towards the house to start a fire, not only to warm myself, but to feel a sense of purpose. It had been quite some time since I had last been this isolated and I hoped I would adjust quickly. Then it happened, that sound, at first so faint most ears would have thought it was just the wind, but I knew this sound as well as my own voice. The moans grew louder, the pitch suddenly imitating a forgotten violin that had not been played in years, yearning to finally be heard. My walk to the house now turned to a run back to the lab. I flew through the door just in time to hear a massive explosion, 2 humpback whales burst into my sight from the patio door.

These feeding companions had come from nowhere and now were just meters from my door step. I am not even sure how my camera came to be in my hands so quickly, guided by intuition I had the first whale in my view finder and clicked just in time to get an ID picture. I spoke out loud to no one “Yes” it was Tornado, a seasonal resident humpback whale, by his side another whale but not one I had ever seen before. I was just catching my breath when I could see a circle of bubbles forming 50 meters from the deck of the lab. When they surfaced it was then that I noticed this was not 2 but 3 humpback whales. They continued to feed along the shore towards the west in Taylor Bight. The rest of the day was filled with the sound of humpback whale feeding calls as 4 individual groups enjoyed a community feast. Oh, and that lonely feeling, completely gone!

The Globe and Mail Article

Below is a link to an article in the Globe and Mail about our work here on Gil Island. This is also a great opportunity, at the end of the article to comment on the Enbridge Northern Gateway Project and to say "NO" to oil tankers travelling the coast line of British Columbia.

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/british-columbia/from-gil-island-perch-couple-study-whales/article1746611/

From Gil Island perch, couple study whales

Wendy Stueck

Gil Island, B.C.— From Thursday's Globe and Mail

The bubbles are the giveaway.

Popping in a swimming-pool-sized ring in front of Gil Island off British Columbia’s northwest coast, the bubbles are signs of humpback whales below, expelling columns of air through their blow holes to herd fish into a tightening circle. The team effort pays off when the whales burst through the middle of the ring, mouths agape, to feast on their prey.

From an aluminum boat about 100 metres away, Janie Wray logs the time of the “bubble-net” feeding and the number of whales. It’s a routine she’s performed hundreds of times since she and her husband, Hermann Meuter, began monitoring whales around Gil Island nearly a decade ago.

Without official connections to major research institutions, the couple is outside the tent of academic cetacean

The $5.5-billion Enbridge Northern Gateway Project would run twinned pipelines from near Edmonton to a marine terminal in Kitimat, B.C., from which tankers would carry oil and condensate up and down Douglas Channel and past Gil Island. The project would add more than 200 tankers a year to the hundreds of cruise ships, fishing boats and barges that ply these waters. For Ms. Wray, the outcome would be predictable, and bleak.

“If those oil tankers go through, I am positive they will hit whales,” Ms. Wray said. “I just don’t see how they won’t.”

Whale strikes are relatively rare; when a cruise ship pulled in to Vancouver in July, 2009, with a dead fin whale impaled on its bow, the incident was front-page news. An Enbridge environmental assessment lists several potential effects of the project on marine mammals, including “behavioural disturbance” among whales resulting from trying to avoid the sounds of dredging and pile drilling, potential injuries from underwater blasting, and potential collisions. All are “currently being assessed.”

Ms. Wray and Mr. Meuter didn’t go looking for tankers. They met as colleagues at OrcaLab, which was set up in 1970 on Hanson Island, off the east coast of Vancouver Island, by pioneering whale researcher Paul Spong. Using hydrophones and video monitoring stations, OrcaLab honed the study of killer whales in the wild.

Inspired, Ms. Wray and Mr. Meuter headed up the coast to find their own whale-study niche. They chose the north coast for its potential to shed light on whales’ winter habits, and hunkered down on Gil Island after getting permission from Gitga’at

In their first season, they lived in a tent.

Since then, with help from friends and patrons – including a benefactor who contributed funds after dropping in from King Pacific Lodge, a high-end floating resort that operates in summer – Ms. Wray and Mr. Meuter have built a year-round base.

A micro-hydro plant on a creek generates electricity. Driftwood, chopped and stacked in piles the size of railway cargo containers fuels wood stoves. There’s an outhouse and sinks with cold running water. Supplies come by boat or float plane. Garbage and recycling go out the same way.

The venture, dubbed Cetacealab and launched in 2001, is a registered charity. To date, the couple has focused on identifying and photographing whales in the area, co-operating with scientists at Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Ms. Wray is working on a submission to an academic journal about resurgent humpback populations in the area.

They have recently stepped up their efforts, hosting student volunteers for the first time over the summer and working to install another hydrophone to create a ring of five listening stations that will cover passes and channels most travelled by humpbacks and orcas and now being considered as tanker routes.

“The advantage of their study is that they are there year-round,” says John Ford, head of DFO’s Cetacean Research Program, adding that DFO has used information gathered by the Gil Island outpost in studies relating to critical whale habitat.

Humpback, fin and killer whales are listed as “threatened” species under Canada’s Species at Risk Act.

As the Enbridge proposal moves through the regulatory process, whales will be part of a much bigger picture – one involving two provinces, about 50 Indian communities, tunnels bored through mountains and two pipelines, each nearly 1,200 kilometres long. Enbridge has filed eight volumes of material with federal regulators touching on everything from double-hulled tanker design to geotechnical studies. Submissions include provisions for tankers to slow down if whales are in the area.

The company’s plans focus on shipping lanes and boundaries that don’t exist for whales, Mr. Meuter said.

“If you have a catastrophic spill here, it will affect the population down the coast,” he said. “They do not stay in Caamano

Please follow the link above to comment on this article at the Globe and Mail

Calm after the Storm

Winter set in early through the waters that surround Gil Island. When we read the forecast 5 days ago we decided we had better beach the boat and lean towards the side of being cautious. They were predicting storm to hurricane force wind, with one major system arriving directly after the other. By the time the 2nd system hit, we were extremely grateful we had listened to our instinct. Up to 55 knot winds sent ripples of vibration through the lab; we were not sure if this was weather or an actual earthquake quivering below our feet.

With increasing intensity each wave crashed on to the rocks, revealing to us the true artist responsible for the many contours and crevices that exist in these ancient formations. We stood in awe, staring towards the sea, watching whirlpools of wind dance between these rising waves of natural energy, sometimes mistaking this upward motion of water to be the blow of a humpback. As the storm continued and we watched the tide rise higher and higher, we could not help but wonder how the posts that hold up the lab would hold with such demanding pressure smashing where wood meets concrete. This was about to be our first test in regards to the engineering behind this precious structure that has only stood on these rocks for just over a year. Fortunately, Hermann has the foresight to build a small cement break way in front of the main posts. As we watched each wave hit with the force of thunder all worries evaporated and were replaced with a sense of contentment. The lab would be holding strong for many more years to come as we search from the shores of Whale Point for that blessed moment when we can say “I see a blow!”

Once the wind finally decided enough was enough and calmness enveloped our home a large sigh was heard from all. We were shocked by the amount of kelp that must have been ripped out from this early storm. Surrounding our boat was not water but a structure of hundreds of bull head kelp, braided together from the twisting seas of yesterday. Both Hermann and I wondered how we were ever going to get the boat off this beach!

Wind and Whales

A young humpback whale showing the world "I am here"

The night before our whale survey I had said “so, tomorrow lets try to be on the water no later than 7:30am.” To my delight it was exactly 7:27am when we pulled off the rocks and were on our way north. The water was flat, the sun was just about to rise behind Princess Royal Island to the east and we were completely geared up to circumnavigate Gil island in search of whales. As we made the turn north into Squally Channel it became immediately obvious we would be changing our plans. The wind was already howling and the waves rippling with white caps. No worries, we would take Whale Channel instead. That turned out to be just wishful thinking as the outflow winds were already pouring down that channel making travel in our small boat completely impossible. Just as we were feeling the tugs of frustration Jessie called us on the radio from Whale Point. She had just spotted a mom and calf humpback near Ashdown Island, which was just minutes from our location and completely wind free. Just as we approached this group we realized another whale had the same idea, though I am sure with a completely different intent than ours. It was a juvenile humpback, and travelling with him was a group of 8 young sea lions. The little calf appeared to be thrilled by this encounter and soon all were rolling, tails splashing, sea lions grunting and speeding through this group of active humpback playtime. Mom also joined in and soon we found ourselves giggling away, completely preoccupied with this magical moment. A few times the juvenile whale would throw his tail so high into the air we were sure he was about to exhibit a complete back flip. The mother turned out to be “ Barnard” a seasonal resident and very well known in these waters. I wondered if there was any relationship between her and this younger whale that was so determined to accompany Barnard and her new calf. Could this be a calf of hers from a few years ago? As we left this trio of whales once again we found ourselves with more questions than answers, knowing the mystery of their ways will continue to inspire our need to understand.

Blog

Blog